What Did Animals Look Like Before Domestication

What Did Animals Look Like Before Domestication

The domestication of animals is the mutual relationship between animals and the humans who have influence on their care and reproduction. [1]

Charles Darwin recognized a small number of traits that fabricated domesticated species dissimilar from their wild ancestors. He was also the starting time to recognize the deviation between conscious selective breeding in which humans directly select for desirable traits, and unconscious selection where traits evolve as a past-product of natural choice or from selection on other traits. [two] [3] [4] There is a genetic difference between domestic and wild populations. In that location is besides a genetic difference between the domestication traits that researchers believe to have been essential at the early stages of domestication, and the improvement traits that have appeared since the split between wild and domestic populations. [5] [6] [7] Domestication traits are more often than not fixed within all domesticates, and were selected during the initial episode of domestication of that animal or constitute, whereas improvement traits are nowadays merely in a proportion of domesticates, though they may be fixed in individual breeds or regional populations. [6] [7] [8]

Domestication should not be dislocated with taming. Taming is the conditioned behavioral modification of a wild-born animal when its natural avoidance of humans is reduced and it accepts the presence of humans, simply domestication is the permanent genetic modification of a bred lineage that leads to an inherited predisposition toward humans. [ix] [x] [eleven] Certain beast species, and certain individuals inside those species, make better candidates for domestication than others considering they showroom sure behavioral characteristics: (one) the size and system of their social structure; (two) the availability and the degree of selectivity in their option of mates; (iii) the ease and speed with which the parents bail with their young, and the maturity and mobility of the young at birth; (4) the degree of flexibility in diet and habitat tolerance; and (v) responses to humans and new environments, including flying responses and reactivity to external stimuli. [12] : Fig 1 [thirteen] [xiv] [15]

It is proposed that in that location were three major pathways that almost animal domesticates followed into domestication: (1) commensals, adapted to a human niche (e.g., dogs, cats, fowl, maybe pigs); (2) prey animals sought for food (eastward.g., sheep, goats, cattle, water buffalo, yak, sus scrofa, reindeer, llama, alpaca, and turkey); and (3) targeted animals for draft and nonfood resources (e.m., horse, donkey, camel). [7] [12] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] The canis familiaris was the get-go to be domesticated, [23] [24] and was established across Eurasia before the end of the Late Pleistocene era, well before cultivation and before the domestication of other animals. [23] Unlike other domestic species which were primarily selected for production-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors. [25] [26] The archaeological and genetic data advise that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks – including donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common. [7] [17] One study has concluded that human selection for domestic traits likely counteracted the homogenizing effect of factor period from wild boars into pigs and created domestication islands in the genome. The same process may also apply to other domesticated animals.Some of the well-nigh commonly domesticated animals are cats and dogs. [27] [28]

Definitions [ edit ]

Domestication [ edit ]

Domestication has been defined as "a sustained multi-generational, mutualistic human relationship in which ane organism assumes a significant degree of influence over the reproduction and care of some other organism in order to secure a more predictable supply of a resource of interest, and through which the partner organism gains reward over individuals that remain outside this relationship, thereby benefitting and often increasing the fettle of both the domesticator and the target domesticate." [i] [12] [29] [30] [31] This definition recognizes both the biological and the cultural components of the domestication process and the furnishings on both humans and the domesticated animals and plants. All by definitions of domestication have included a relationship between humans with plants and animals, but their differences lay in who was considered as the lead partner in the relationship. This new definition recognizes a mutualistic relationship in which both partners proceeds benefits. Domestication has vastly enhanced the reproductive output of ingather plants, livestock, and pets far beyond that of their wild progenitors. Domesticates have provided humans with resources that they could more predictably and securely control, move, and redistribute, which has been the reward that had fueled a population explosion of the agro-pastoralists and their spread to all corners of the planet. [12]

This biological mutualism is non restricted to humans with domestic crops and livestock but is well-documented in nonhuman species, particularly amid a number of social insect domesticators and their plant and animal domesticates, for example the ant–fungus mutualism that exists between leafcutter ants and certain fungi. [one]

Domestication syndrome [ edit ]

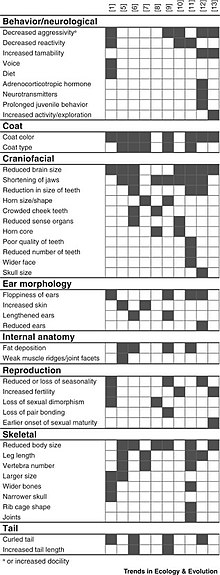

Traits used to define the beast domestication syndrome [32]

Domestication syndrome is a term often used to describe the suite of phenotypic traits arising during domestication that distinguish crops from their wild ancestors. [5] [33] The term is also practical to animals and includes increased docility and tameness, coat color changes, reductions in tooth size, changes in craniofacial morphology, alterations in ear and tail class (e.g., floppy ears), more than frequent and nonseasonal estrus cycles, alterations in adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, changed concentrations of several neurotransmitters, prolongations in juvenile beliefs, and reductions in both total brain size and of particular brain regions. [34] The set up of traits used to define the animal domestication syndrome is inconsistent. [32]

Difference from taming [ edit ]

Domestication should not be confused with taming. Taming is the conditioned behavioral modification of a wild-born animal when its natural avoidance of humans is reduced and information technology accepts the presence of humans, but domestication is the permanent genetic modification of a bred lineage that leads to an inherited predisposition toward humans. [ix] [10] [11] Human selection included tameness, just without a suitable evolutionary response so domestication was not accomplished. [7] Domestic animals need non be tame in the behavioral sense, such as the Spanish fighting balderdash. Wild fauna can be tame, such every bit a paw-raised cheetah. A domestic animate being'due south breeding is controlled by humans and its tameness and tolerance of humans is genetically determined. However, an animal merely bred in captivity is not necessarily domesticated. Tigers, gorillas, and polar bears breed readily in captivity just are not domesticated. [10] Asian elephants are wild fauna that with taming manifest outward signs of domestication, yet their convenance is not human controlled and thus they are not truthful domesticates. [ten] [35]

History, cause and timing [ edit ]

Development of temperatures in the postglacial menstruation, after the Final Glacial Maximum, showing very low temperatures for the most part of the Younger Dryas, rapidly rising afterwards to achieve the level of the warm Holocene, based on Greenland ice cores. [36]

The domestication of animals and plants was triggered past the climatic and ecology changes that occurred after the peak of the Final Glacial Maximum around 21,000 years ago and which continue to this nowadays mean solar day. These changes made obtaining food difficult. The first domesticate was the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) from a wolf ancestor (Canis lupus) at least 15,000 years ago. The Younger Dryas that occurred 12,900 years ago was a period of intense cold and aridity that put force per unit area on humans to intensify their foraging strategies. Past the starting time of the Holocene from 11,700 years agone, favorable climatic conditions and increasing human being populations led to pocket-size-scale animal and plant domestication, which allowed humans to augment the food that they were obtaining through hunter-gathering. [37]

The increased employ of agriculture and connected domestication of species during the Neolithic transition marked the beginning of a rapid shift in the evolution, ecology, and demography of both humans and numerous species of animals and plants. [38] [seven] Areas with increasing agriculture, underwent urbanisation, [38] [39] developing higher-density populations, [38] [xl] expanded economies, and became centers of livestock and crop domestication. [38] [41] [42] Such agronomical societies emerged across Eurasia, North Africa, and South and Cardinal America.

In the Fertile Crescent x,000-11,000 years agone, zooarchaeology indicates that goats, pigs, sheep, and taurine cattle were the first livestock to be domesticated. Archaeologists working in Cyprus constitute an older burying basis, approximately 9500 years one-time, of an adult man with a feline skeleton. [43] Two thousand years later, humped zebu cattle were domesticated in what is today Baluchistan in Pakistan. In East Asia 8,000 years agone, pigs were domesticated from wild boar that were genetically unlike from those found in the Fertile Crescent. The horse was domesticated on the Central Asian steppe five,500 years ago. The chicken in Southeast Asia was domesticated iv,000 years ago. [37]

Universal features [ edit ]

The biomass of wild vertebrates is now increasingly pocket-size compared to the biomass of domestic animals, with the calculated biomass of domestic cattle solitary beingness greater than that of all wild mammals. [44] Because the evolution of domestic animals is ongoing, the process of domestication has a beginning but non an cease. Various criteria have been established to provide a definition of domestic animals, but all decisions about exactly when an animal can be labelled "domesticated" in the zoological sense are arbitrary, although potentially useful. [45] Domestication is a fluid and nonlinear process that may kickoff, stop, reverse, or get down unexpected paths with no clear or universal threshold that separates the wild from the domestic. However, at that place are universal features held in common by all domesticated animals. [12]

Behavioral preadaption [ edit ]

Sure animal species, and certain individuals within those species, make better candidates for domestication than others because they exhibit certain behavioral characteristics: (ane) the size and organization of their social structure; (two) the availability and the degree of selectivity in their choice of mates; (3) the ease and speed with which the parents bond with their young, and the maturity and mobility of the young at birth; (iv) the degree of flexibility in nutrition and habitat tolerance; and (5) responses to humans and new environments, including flight responses and reactivity to external stimuli. [12] : Fig 1 [13] [14] [15] Reduced wariness to humans and low reactivity to both humans and other external stimuli are a key pre-adaptation for domestication, and these behaviors are also the primary target of the selective pressures experienced by the animal undergoing domestication. [7] [12] This implies that non all animals can exist domesticated, eastward.g. a wild member of the horse family, the zebra. [7] [42]

Jared Diamond in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel enquired as to why, among the globe'southward 148 large wild terrestrial herbivorous mammals, but xiv were domesticated, and proposed that their wild ancestors must take possessed half-dozen characteristics before they could be considered for domestication: [iii] : p168-174

- Efficient diet – Animals that can efficiently process what they swallow and live off plants are less expensive to proceed in captivity. Carnivores feed on mankind, which would require the domesticators to raise additional animals to feed the carnivores and therefore increase the consumption of plants further.

- Quick growth charge per unit – Fast maturity charge per unit compared to the man life span allows breeding intervention and makes the animal useful within an acceptable duration of caretaking. Some large animals require many years before they reach a useful size.

- Power to brood in captivity – Animals that volition non breed in captivity are limited to acquisition through capture in the wild.

- Pleasant disposition – Animals with nasty dispositions are unsafe to proceed effectually humans.

- Tendency not to panic – Some species are nervous, fast, and prone to flight when they perceive a threat.

- Social structure – All species of domesticated large mammals had wild ancestors that lived in herds with a dominance hierarchy among the herd members, and the herds had overlapping habitation territories rather than mutually sectional home territories. This arrangement allows humans to take control of the say-so bureaucracy.

Brain size and function [ edit ]

The sustained selection for lowered reactivity among mammal domesticates has resulted in profound changes in encephalon course and function. The larger the size of the encephalon to begin with and the greater its caste of folding, the greater the degree of brain-size reduction under domestication. [12] [46] Foxes that had been selectively bred for tameness over 40 years had experienced a meaning reduction in cranial acme and width and by inference in encephalon size, [12] [47] which supports the hypothesis that encephalon-size reduction is an early response to the selective pressure for tameness and lowered reactivity that is the universal feature of animal domestication. [12] The almost affected portion of the encephalon in domestic mammals is the limbic system, which in domestic dogs, pigs, and sheep show a 40% reduction in size compared with their wild species. This portion of the brain regulates endocrine function that influences behaviors such as aggression, wariness, and responses to environmentally induced stress, all attributes which are dramatically affected past domestication. [12] [46]

Pleiotropy [ edit ]

A putative crusade for the broad changes seen in domestication syndrome is pleiotropy. Pleiotropy occurs when ane cistron influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Certain physiological changes narrate domestic animals of many species. These changes include extensive white markings (particularly on the head), floppy ears, and curly tails. These arise fifty-fifty when tameness is the only trait under selective pressure. [48] The genes involved in tameness are largely unknown, then it is non known how or to what extent pleiotropy contributes to domestication syndrome. Tameness may be caused past the downwardly regulation of fearfulness and stress responses via reduction of the adrenal glands. [48] Based on this, the pleiotropy hypotheses tin exist separated into two theories. The Neural Crest Hypothesis relates adrenal gland role to deficits in neural crest cells during development. The Single Genetic Regulatory Network Hypothesis claims that genetic changes in upstream regulators touch on downstream systems. [49] [fifty]

Neural crest cells (NCC) are vertebrate embryonic stem cells that function direct and indirectly during early embryogenesis to produce many tissue types. [49] Because the traits commonly affected past domestication syndrome are all derived from NCC in development, the neural crest hypothesis suggests that deficits in these cells cause the domain of phenotypes seen in domestication syndrome. [l] These deficits could crusade changes nosotros meet to many domestic mammals, such as lopped ears (seen in rabbit, dog, flim-flam, pig, sheep, caprine animal, cattle, and donkeys) as well equally curly tails (pigs, foxes, and dogs). Although they do not impact the development of the adrenal cortex directly, the neural crest cells may exist involved in relevant upstream embryological interactions. [49] Furthermore, artificial selection targeting tameness may bear on genes that command the concentration or motion of NCCs in the embryo, leading to a multifariousness of phenotypes. [50]

The single genetic regulatory network hypothesis proposes that domestication syndrome results from mutations in genes that regulate the expression design of more downstream genes. [48] For example piebald, or spotted coat coloration, may be acquired past a linkage in the biochemical pathways of melanins involved in coat coloration and neurotransmitters such as dopamine that assist shape behavior and cognition. [12] [51] These linked traits may arise from mutations in a few cardinal regulatory genes. [12] A problem with this hypothesis is that it proposes that there are mutations in gene networks that crusade dramatic effects that are not lethal, however no currently known genetic regulatory networks crusade such dramatic change in so many unlike traits. [49]

Limited reversion [ edit ]

Feral mammals such as dogs, cats, goats, donkeys, pigs, and ferrets that have lived apart from humans for generations show no sign of regaining the brain mass of their wild progenitors. [12] [52] Dingos have lived apart from humans for thousands of years but still accept the same brain size as that of a domestic domestic dog. [12] [53] Feral dogs that actively avoid human being contact are nevertheless dependent on human waste for survival and have non reverted to the cocky-sustaining behaviors of their wolf ancestors. [12] [54]

Categories [ edit ]

Domestication can be considered as the final phase of intensification in the human relationship between animal or plant sub-populations and man societies, but information technology is divided into several grades of intensification. [55] For studies in beast domestication, researchers have proposed five distinct categories: wild, captive wild, domestic, cantankerous-breeds and feral. [15] [56] [57]

- Wild animals

- Field of study to natural selection, although the action of past demographic events and artificial selection induced by game direction or habitat destruction cannot be excluded. [57]

- Captive wild animals

- Directly affected past a relaxation of natural selection associated with feeding, breeding and protection/confinement past humans, and an intensification of artificial selection through passive pick for animals that are more suited to captivity. [57]

- Domestic animals

- Discipline to intensified artificial choice through husbandry practices with relaxation of natural selection associated with captivity and management. [57]

- Cantankerous-breed animals

- Genetic hybrids of wild and domestic parents. They may be forms intermediate between both parents, forms more than similar to one parent than the other, or unique forms distinct from both parents. Hybrids can be intentionally bred for specific characteristics or can ascend unintentionally as the result of contact with wild individuals. [57]

- Feral animals

- Domesticates that accept returned to a wild state. As such, they feel relaxed artificial selection induced past the captive environment paired with intensified natural option induced by the wild habitat. [57]

In 2015, a study compared the diverseness of dental size, shape and allometry across the proposed domestication categories of modern pigs (genus Sus). The report showed clear differences between the dental phenotypes of wild, captive wild, domestic, and hybrid pig populations, which supported the proposed categories through physical evidence. The study did not embrace feral pig populations but chosen for farther enquiry to exist undertaken on them, and on the genetic differences with hybrid pigs. [57]

Pathways [ edit ]

Since 2012, a multi-stage model of animal domestication has been accepted by two groups. The beginning group proposed that animal domestication proceeded along a continuum of stages from anthropophily, commensalism, control in the wild, control of convict animals, extensive breeding, intensive convenance, and finally to pets in a dull, gradually intensifying human relationship between humans and animals. [45] [55]

The second group proposed that in that location were three major pathways that most animal domesticates followed into domestication: (1) commensals, adapted to a human niche (e.g., dogs, cats, fowl, perhaps pigs); (2) prey animals sought for food (due east.g., sheep, goats, cattle, h2o buffalo, yak, pig, reindeer, llama and alpaca); and (three) targeted animals for draft and nonfood resource (e.m., horse, donkey, camel). [vii] [12] [16] [17] [eighteen] [19] [twenty] [21] [22] The ancestry of creature domestication involved a protracted coevolutionary process with multiple stages forth unlike pathways. Humans did non intend to domesticate animals from, or at to the lowest degree they did not envision a domesticated animal resulting from, either the commensal or prey pathways. In both of these cases, humans became entangled with these species as the human relationship between them, and the human role in their survival and reproduction, intensified. [7] Although the directed pathway proceeded from capture to taming, the other two pathways are non as goal-oriented and archaeological records suggest that they take place over much longer time frames. [45]

Commensal pathway [ edit ]

The commensal pathway was traveled by vertebrates that fed on refuse around human habitats or by animals that preyed on other animals drawn to man camps. Those animals established a commensal human relationship with humans in which the animals benefited but the humans received no impairment but petty benefit. Those animals that were most capable of taking advantage of the resources associated with human camps would accept been the tamer, less aggressive individuals with shorter fight or flight distances. [58] [59] [60] Later, these animals developed closer social or economical bonds with humans that led to a domestic human relationship. [seven] [12] [16] The leap from a synanthropic population to a domestic i could only have taken place after the animals had progressed from anthropophily to habituation, to commensalism and partnership, when the relationship between animal and human would have laid the foundation for domestication, including captivity and human-controlled breeding. From this perspective, animal domestication is a coevolutionary process in which a population responds to selective pressure while adapting to a novel niche that included another species with evolving behaviors. [vii] Commensal pathway animals include dogs, cats, fowl, and possibly pigs. [23]

The domestication of animals commenced over xv,000years before present (YBP), beginning with the grayness wolf (Canis lupus) by nomadic hunter-gatherers. It was not until 11,000 YBP that people living in the Most E entered into relationships with wild populations of aurochs, boar, sheep, and goats. A domestication procedure then began to develop. The grey wolf well-nigh likely followed the commensal pathway to domestication. When, where, and how many times wolves may have been domesticated remains debated because only a small number of ancient specimens have been found, and both archæology and genetics proceed to provide conflicting evidence. The almost widely accepted, earliest dog remains date dorsum 15,000 YBP to the Bonn–Oberkassel dog. Before remains dating back to 30,000 YBP take been described equally Paleolithic dogs, however their status as dogs or wolves remains debated. Recent studies indicate that a genetic divergence occurred between dogs and wolves 20,000–40,000 YBP, even so this is the upper time-limit for domestication because it represents the time of divergence and not the fourth dimension of domestication. [61]

The chicken is one of the most widespread domesticated species and 1 of the human being world's largest sources of protein. Although the chicken was domesticated in S-East asia, archaeological bear witness suggests that information technology was not kept equally a livestock species until 400BCE in the Levant. [62] Prior to this, chickens had been associated with humans for thousands of years and kept for cock-fighting, rituals, and majestic zoos, so they were non originally a prey species. [62] [63] The chicken was not a popular food in Europe until only one thousand years ago. [64]

Casualty pathway [ edit ]

The prey pathway was the fashion in which most major livestock species entered into domestication as these were once hunted by humans for their meat. Domestication was likely initiated when humans began to experiment with hunting strategies designed to increase the availability of these prey, perhaps as a response to localized pressure on the supply of the creature. Over time and with the more responsive species, these game-management strategies adult into herd-direction strategies that included the sustained multi-generational command over the animals' movement, feeding, and reproduction. As man interference in the life-cycles of prey animals intensified, the evolutionary pressures for a lack of aggression would have led to an conquering of the same domestication syndrome traits constitute in the commensal domesticates. [vii] [12] [16]

Prey pathway animals include sheep, goats, cattle, water buffalo, yak, squealer, reindeer, llama and alpaca. The right conditions for the domestication for some of them appear to have been in place in the central and eastern Fertile Crescent at the end of the Younger Dryas climatic downturn and the beginning of the Early Holocene about 11,700 YBP, and by 10,000 YBP people were preferentially killing young males of a multifariousness of species and allowed the females to alive in society to produce more than offspring. [7] [12] By measuring the size, sex ratios, and mortality profiles of zooarchaeological specimens, archeologists have been able to document changes in the management strategies of hunted sheep, goats, pigs, and cows in the Fertile Crescent starting 11,700 YBP. A recent demographic and metrical study of moo-cow and grunter remains at Sha'ar Hagolan, Israel, demonstrated that both species were severely overhunted before domestication, suggesting that the intensive exploitation led to management strategies adopted throughout the region that ultimately led to the domestication of these populations post-obit the casualty pathway. This design of overhunting earlier domestication suggests that the prey pathway was as adventitious and unintentional as the commensal pathway. [7] [16]

Directed pathway [ edit ]

The directed pathway was a more deliberate and directed procedure initiated by humans with the goal of domesticating a free-living animal. It probably merely came into existence once people were familiar with either commensal or prey-pathway domesticated animals. These animals were probable non to possess many of the behavioral preadaptions some species bear witness before domestication. Therefore, the domestication of these animals requires more than deliberate endeavour by humans to work around behaviors that practice not assist domestication, with increased technological assistance needed. [vii] [12] [16]

Humans were already reliant on domestic plants and animals when they imagined the domestic versions of wild animals. Although horses, donkeys, and Onetime Globe camels were sometimes hunted as prey species, they were each deliberately brought into the human niche for sources of send. Domestication was still a multi-generational adaptation to human selection pressures, including tameness, but without a suitable evolutionary response then domestication was not achieved. [7] For example, despite the fact that hunters of the Nearly Eastern gazelle in the Epipaleolithic avoided culling reproductive females to promote population residual, neither gazelles [7] [42] nor zebras [vii] [65] possessed the necessary prerequisites and were never domesticated. In that location is no articulate evidence for the domestication of any herded prey animal in Africa, [seven] with the notable exception of the donkey, which was domesticated in Northeast Africa sometime in the fourth millennium BCE. [66]

Multiple pathways [ edit ]

The pathways that animals may take followed are not mutually exclusive. Pigs, for case, may have been domesticated as their populations became accustomed to the human niche, which would suggest a commensal pathway, or they may accept been hunted and followed a prey pathway, or both. [7] [12] [16]

Post-domestication gene flow [ edit ]

Equally agricultural societies migrated away from the domestication centers taking their domestic partners with them, they encountered populations of wild animals of the same or sister species. Because domestics often shared a recent common antecedent with the wild populations, they were capable of producing fertile offspring. Domestic populations were pocket-sized relative to the surrounding wild populations, and repeated hybridizations between the two eventually led to the domestic population condign more genetically divergent from its original domestic source population. [45] [67]

Advances in Deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing engineering science permit the nuclear genome to be accessed and analyzed in a population genetics framework. The increased resolution of nuclear sequences has demonstrated that factor period is mutual, not only between geographically various domestic populations of the same species but also between domestic populations and wild species that never gave rise to a domestic population. [7]

- The yellow leg trait possessed past numerous modernistic commercial chicken breeds was acquired via introgression from the greyness junglefowl indigenous to South Asia. [seven] [68]

- African cattle are hybrids that possess both a European Taurine cattle maternal mitochondrial betoken and an Asian Indicine cattle paternal Y-chromosome signature. [7] [69]

- Numerous other bovid species, including bison, yak, banteng, and gaur also hybridize with ease. [seven] [seventy]

- Cats [7] [71] and horses [7] [72] have been shown to hybridize with many closely related species.

- Domestic dear bees accept mated with so many unlike species they now possess genomes more variable than their original wild progenitors. [7] [73]

The archaeological and genetic data suggests that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks – including canids, donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common. [seven] [17] Bidirectional cistron flow between domestic and wild reindeer continues today. [7]

The consequence of this introgression is that modernistic domestic populations can often appear to accept much greater genomic affinity to wild populations that were never involved in the original domestication process. Therefore, information technology is proposed that the term "domestication" should be reserved solely for the initial process of domestication of a detached population in time and infinite. Subsequent admixture betwixt introduced domestic populations and local wild populations that were never domesticated should be referred to as "introgressive capture". Conflating these 2 processes muddles our understanding of the original process and can lead to an artificial inflation of the number of times domestication took place. [seven] [45] This introgression can, in some cases, be regarded as adaptive introgression, as observed in domestic sheep due to factor period with the wild European Mouflon. [74]

The sustained admixture between different dog and wolf populations across the Sometime and New Worlds over at to the lowest degree the concluding 10,000 years has blurred the genetic signatures and confounded efforts of researchers at pinpointing the origins of dogs. [23] None of the modern wolf populations are related to the Pleistocene wolves that were first domesticated, [7] [75] and the extinction of the wolves that were the direct ancestors of dogs has muddied efforts to pinpoint the fourth dimension and place of dog domestication. [7]

Positive selection [ edit ]

Charles Darwin recognized the minor number of traits that fabricated domestic species different from their wild ancestors. He was also the starting time to recognize the departure betwixt conscious selective breeding in which humans straight select for desirable traits, and unconscious selection where traits evolve as a by-product of natural selection or from pick on other traits. [2] [3] [four]

Domestic animals have variations in glaze color and craniofacial morphology, reduced encephalon size, floppy ears, and changes in the endocrine system and their reproductive wheel. The domesticated argent fox experiment demonstrated that pick for tameness within a few generations can result in modified behavioral, morphological, and physiological traits. [38] [45] In addition to demonstrating that domestic phenotypic traits could arise through selection for a behavioral trait, and domestic behavioral traits could ascend through the selection for a phenotypic trait, these experiments provided a mechanism to explicate how the animal domestication process could have begun without deliberate homo forethought and action. [45] In the 1980s, a researcher used a set of behavioral, cerebral, and visible phenotypic markers, such every bit glaze colour, to produce domesticated dormant deer within a few generations. [45] [76] Similar results for tameness and fear accept been found for mink [77] and Japanese quail. [78]

The genetic difference between domestic and wild populations tin can be framed inside 2 considerations. The first distinguishes between domestication traits that are presumed to have been essential at the early stages of domestication, and improvement traits that take appeared since the split betwixt wild and domestic populations. [v] [6] [7] Domestication traits are by and large fixed within all domesticates and were selected during the initial episode of domestication, whereas comeback traits are nowadays only in a proportion of domesticates, though they may be fixed in individual breeds or regional populations. [6] [7] [8] A second issue is whether traits associated with the domestication syndrome resulted from a relaxation of selection as animals exited the wild surroundings or from positive pick resulting from intentional and unintentional man preference. Some contempo genomic studies on the genetic ground of traits associated with the domestication syndrome accept shed low-cal on both of these bug. [7]

Geneticists take identified more than 300 genetic loci and 150 genes associated with coat color variability. [45] [79] Knowing the mutations associated with different colors has allowed some correlation between the timing of the advent of variable coat colors in horses with the timing of their domestication. [45] [lxxx] Other studies have shown how human-induced choice is responsible for the allelic variation in pigs. [45] [81] Together, these insights suggest that, although natural selection has kept variation to a minimum before domestication, humans have actively selected for novel coat colors equally soon as they appeared in managed populations. [45] [51]

In 2015, a report looked at over 100 pig genome sequences to ascertain their procedure of domestication. The process of domestication was causeless to take been initiated by humans, involved few individuals and relied on reproductive isolation between wild and domestic forms, simply the written report found that the assumption of reproductive isolation with population bottlenecks was non supported. The study indicated that pigs were domesticated separately in Southwest asia and China, with Western Asian pigs introduced into Europe where they crossed with wild boar. A model that fitted the information included admixture with a now extinct ghost population of wild pigs during the Pleistocene. The study besides constitute that despite dorsum-crossing with wild pigs, the genomes of domestic pigs have strong signatures of choice at genetic loci that affect behavior and morphology. The study ended that man choice for domestic traits likely counteracted the homogenizing issue of gene flow from wild boars and created domestication islands in the genome. The same process may besides utilize to other domesticated animals. [27] [28]

Dissimilar other domestic species which were primarily selected for product-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors. [25] [26] In 2016, a report plant that there were only 11 stock-still genes that showed variation betwixt wolves and dogs. These factor variations were unlikely to have been the consequence of natural development, and signal selection on both morphology and behavior during dog domestication. These genes have been shown to affect the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response [26] [82] (i.e. selection for tameness), and emotional processing. [26] Dogs generally show reduced fright and assailment compared to wolves. [26] [83] Some of these genes have been associated with aggression in some dog breeds, indicating their importance in both the initial domestication and so later in breed germination. [26]

Meet also [ edit ]

- List of domesticated animals

- Hybrid (biology)#Examples of hybrid animals and animate being populations derived from hybrid

- Landrace

References [ edit ]

- ^ a b c Zeder, 1000. A. (2015). "Core questions in domestication Inquiry". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of America. 112 (11): 3191–3198. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.3191Z. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501711112 . PMC 4371924 . PMID25713127.

- ^ a b Darwin, Charles (1868). The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication . London: John Murray. OCLC156100686.

- ^ a b c Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel . London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 978-0-09-930278-0 .

- ^ a b Larson, Yard.; Piperno, D. R.; Allaby, R. 1000.; Purugganan, M. D.; Andersson, L.; Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Barton, L.; Climer Vigueira, C.; Denham, T.; Dobney, K.; Doust, A. N.; Gepts, Paul; Gilbert, Yard. T. P.; Gremillion, K. J.; Lucas, L.; Lukens, 50.; Marshall, F. B.; Olsen, K. M.; Pires, J. C.; Richerson, P. J.; Rubio De Casas, R.; Sanjur, O. I.; Thomas, Chiliad. G.; Fuller, D. Q. (2014). "Current perspectives and the hereafter of domestication studies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6139–6146. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6139L. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323964111 . PMC 4035915 . PMID24757054.

- ^ a b c Olsen, K. Yard.; Wendel, J. F. (2013). "A bountiful harvest: genomic insights into ingather domestication phenotypes". Almanac Review of Plant Biology. 64: 47–seventy. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120048. PMID23451788.

- ^ a b c d Doust, A. N.; Lukens, L.; Olsen, K. M.; Mauro-Herrera, M.; Meyer, A.; Rogers, K. (2014). "Beyond the single gene: How epistasis and cistron-by-environment furnishings influence ingather domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6178–6183. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6178D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308940110 . PMC 4035984 . PMID24753598.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k l m northward o p q r south t u v w ten y z aa ab air-conditioning ad ae af ag ah ai aj Larson, One thousand. (2014). "The Development of Animal Domestication" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Development, and Systematics. 45: 115–36. doi:x.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135813.

- ^ a b Meyer, Rachel S.; Purugganan, Michael D. (2013). "Evolution of crop species: Genetics of domestication and diversification". Nature Reviews Genetics. 14 (12): 840–52. doi:x.1038/nrg3605. PMID24240513. S2CID529535.

- ^ a b Cost, Edward O. (2008). Principles and Applications of Domestic Animate being Beliefs: An Introductory Text . Cambridge University Printing. ISBN 9781780640556 . Retrieved Jan 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Driscoll, C. A.; MacDonald, D. Due west.; O'Brien, Due south. J. (2009). "From wildlife to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106: 9971–9978. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9971D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901586106 . PMC 2702791 . PMID19528637.

- ^ a b Diamond, Jared (2012). "1". In Gepts, Paul (ed.). Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability. Cambridge University Press. p. xiii.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j k fifty k n o p q r due south t u v Zeder, M. A. (2012). "The domestication of animals". Journal of Anthropological Inquiry. 68 (2): 161–190. doi:x.3998/jar.0521004.0068.201. S2CID85348232.

- ^ a b Unhurt, E. B. (1969). "Domestication and the evolution of behavior". In Hafez, E. South. E. (ed.). The Beliefs of Domestic Animals (2nd ed.). London: Bailliere, Tindall, and Cassell. pp. 22–42.

- ^ a b Toll, Edward O. (1984). "Behavioral aspects of fauna domestication". Quarterly Review of Biology. 59 (ane): ane–32. doi:10.1086/413673. JSTOR2827868. S2CID83908518.

- ^ a b c Price, Edward O. (2002). Animal Domestication and Beliefs (PDF). Wallingford, England: CABI Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2016-02-26 .

- ^ a b c d e f g Frantz, L. (2015). "The Evolution of Suidae". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 4: 61–85. doi:ten.1146/annurev-brute-021815-111155. PMID26526544.

- ^ a b c d Marshall, F. (2013). "Evaluating the roles of directed breeding and gene menstruum in animate being domestication". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the Usa of America. 111 (17): 6153–6158. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6153M. doi: ten.1073/pnas.1312984110 . PMC 4035985 . PMID24753599.

- ^ a b Blaustein, R. (2015). "Unraveling the Mysteries of Animate being Domestication: Whole-genome sequencing challenges old assumptions". BioScience. 65 (1): 7–13. doi: x.1093/biosci/biu201 .

- ^ a b Telechea, F. (2015). "Domestication and genetics". In Pontaroti, P. (ed.). Evolutionary Biology: Biodiversification from Genotype to Phenotype. Springer. p. 397.

- ^ a b Vahabi, M. (2015). "Human species as the primary predator". The Political Economy of Predation: Manhunting and the Economics of Escape. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9781107133976 .

- ^ a b Gepts, Paul, ed. (2012). "9". Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability. Cambridge University Printing. pp. 227–259.

- ^ a b Pontarotti, Pierre, ed. (2015). Evolutionary Biology: Biodiversification from Genotype to Phenotype. Springer International. p. 397.

- ^ a b c d Larson, G. (2012). "Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography" (PDF). Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United states of america of America. 109 (23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi: ten.1073/pnas.1203005109 . PMC 3384140 . PMID22615366.

- ^ Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation". Journal of Archaeological Scientific discipline. 68: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- ^ a b Serpell, J.; Duffy, D. (2014). "Dog Breeds and Their Behavior". Canis familiaris Cognition and Behavior. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer.

- ^ a b c d e f Cagan, Alex; Blass, Torsten (2016). "Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by selection during dog domestication". BMC Evolutionary Biology. sixteen: 10. doi:x.1186/s12862-015-0579-7. PMC 4710014 . PMID26754411.

- ^ a b c Frantz, L. (2015). "Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic grunter genomes". Nature Genetics. 47 (x): 1141–1148. doi:10.1038/ng.3394. PMID26323058. S2CID205350534.

- ^ a b c Pennisi, E. (2015). "The taming of the grunter took some wild turns". Science . doi:10.1126/science.aad1692.

- ^ Maggioni, Lorenzo (2015). "Domestication of Brassica oleracea L.". Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae: 38.

- ^ Zeder, One thousand. (2014). "Domestication: Definition and Overview". In Smith, Claire (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 2184–2194. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_71. ISBN 978-ane-4419-0426-3 .

- ^ Sykes, Naomi (2014). "Animal Revolutions". Beastly Questions: Fauna Answers to Archaeological Bug. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9781472506245 .

- ^ a b Lord KA, Larson G, Coppinger RP, Karlsson EK (February 2022). "The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Beast Domestication Syndrome". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (two): 125–136. doi: ten.1016/j.tree.2022.x.011 . PMID31810775.

- ^ Hammer, Chiliad. (1984). "Das Domestikationssyndrom". Kulturpflanze. 32: eleven–34. doi:10.1007/bf02098682. S2CID42389667.

- ^ Wilkins, Adam Due south.; Wrangham, Richard West.; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (July 2014). "The 'Domestication Syndrome' in Mammals: A Unified Caption Based on Neural Crest Cell Behavior and Genetics". Genetics . 197 (three): 795–808. doi:ten.1534/genetics.114.165423. PMC 4096361 . PMID25024034.

- ^ Lair, R. C. (1997). Gone Astray: The Care and Management of the Asian Elephant in Domesticity. Bangkok: Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

- ^ Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (6 January 2017). "Mapping Postal service-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of Southwest Asia". Scientific Reports. 7: 40338. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:ten.1038/srep40338. ISSN2045-2322. PMC 5216412 . PMID28059138.

- ^ a b McHugo, Gillian P.; Dover, Michael J.; Machugh, David E. (2022). "Unlocking the origins and biology of domestic animals using ancient DNA and paleogenomics". BMC Biology. 17 (1): 98. doi:ten.1186/s12915-019-0724-7. PMC 6889691 . PMID31791340.

- ^ a b c d due east Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). "Taming the Past: Ancient Deoxyribonucleic acid and the Study of Animal Domestication". Annual Review of Brute Biosciences. 5: 329–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-animate being-022516-022747. PMID27813680.

- ^ Barker, G. (2006). The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers?. Oxford University Press. [ page needed ]

- ^ Bocquet-Appel, J. P. (2011). "When the world's population took off: The springboard of the Neolithic Demographic Transition". Science . 333 (6042): 560–561. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..560B. doi:10.1126/science.1208880. PMID21798934. S2CID29655920.

- ^ Fuller DQ, Willcox G, Allaby RG. 2011. Cultivation and domestication had multiple origins: arguments against the core surface area hypothesis for the origins of agriculture in the Near East. World Archaeol. 43:628–52

- ^ a b c Melinda A. Zeder 2006. Archaeological approaches to documenting animal domestication. In Documenting Domestication: New Genetic and Archaeological Paradigms, ed. M.A. Zeder, D.G Bradley, Due east Emshwiller, B.D Smith, pp. 209–27. Berkeley: Univ. Calif. Press

- ^ Driscoll, Carlos; Clutton-Brock, Juliet; Kitchener, Andrew; O'Brien, Stephen (2009 June). "The Taming of the True cat". Sci Am. 300 (6): 68–75. PMID19485091 . Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Valclav Smil, 2011, Harvesting the Biosphere:The Human Impact, Population and Development Review 37(four): 613–636, Table 2)

- ^ a b c d east f k h i j k l Larson, M. (2013). "A population genetics view of animal domestication" (PDF). Trends in Genetics. 29 (4): 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.01.003. PMID23415592.

- ^ a b Kruska, D. 1988. "Mammalian domestication and its effect on brain structure and behavior," in Intelligence and evolutionary biological science. Edited by H. J. Jerison and I. Jerison, pp. 211–50. New York: Springer-Verlag

- ^ Trut, Lyudmila N. (1999). "Early Canid Domestication: The Farm-Flim-flam Experiment" (PDF). American Scientist. 87 (March–April): 160–169. Bibcode:1999AmSci..87.....T. doi:10.1511/1999.2.160. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c Trut, Lyudmila; Oskina, Irina; Kharlamova, Anastasiya (2009). "Animal evolution during domestication: the domesticated trick equally a model". BioEssays. 31 (three): 349–360. doi:ten.1002/bies.200800070. PMC 2763232 . PMID19260016.

- ^ a b c d Wilkins, Adam S.; Wrangham, Richard W.; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2014). "The "Domestication Syndrome" in Mammals: A Unified Explanation Based on Neural Crest Prison cell Beliefs and Genetics". Genetics. 197 (3): 795–808. doi:10.1534/genetics.114.165423. PMC 4096361 . PMID25024034.

- ^ a b c Wright (2015). "The Genetic Architecture of Domestication in Animals". Bioinformatics and Biology Insights. 9S4 (Suppl 4): 11–20. doi:x.4137/bbi.s28902. PMC 4603525 . PMID26512200.

- ^ a b Hemmer, H. (1990). Domestication: The Decline of Environmental Appreciation. Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ Birks, J. D. South., and A. C. Kitchener. 1999. The distribution and condition of the polecat Mustela putorius in U.k. in the 1990s. London: Vincent Wildlife Trust.

- ^ Schultz, W. (1969). "Zur kenntnis des hallstromhundes (Canis hallstromi, Troughton 1957)". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 183: 42–72.

- ^ Boitani, L.; Ciucci, P. (1995). "Comparative social ecology of feral dogs and wolves" (PDF). Ethology Environmental & Evolution. seven (ane): 49–72. doi:10.1080/08927014.1995.9522969.

- ^ a b Vigne, J. D. (2011). "The origins of fauna domestication and husbandry: a major alter in the history of humanity and the biosphere". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 334 (3): 171–181. doi:ten.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.009. PMID21377611.

- ^ Mayer, J. J.; Brisbin, I. Fifty. (1991). Wild Pigs in the United States: Their History, Comparative Morphology, and Current Status. Athens, Georgia, US: University of Georgia Printing.

- ^ a b c d e f g Evin, Allowen; Dobney, Keith; Schafberg, Renate; Owen, Joseph; Vidarsdottir, Una; Larson, Greger; Cucchi, Thomas (2015). "Phenotype and beast domestication: A report of dental variation betwixt domestic, wild, captive, hybrid and insular Pig" (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: half-dozen. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0269-10. PMC 4328033 . PMID25648385.

- ^ Crockford, S. J. (2000). "A commentary on dog evolution: Regional variation, breed development and hybridization with wolves". In Crockford, S. (ed.). Dogs through Time: An Archaeological Perspective. BAR International Series 889. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. eleven–twenty. ISBN 978-1841710891 .

- ^ Coppinger, Raymond; Coppinger, Laura (2001). Dogs: A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior & Evolution . Scribner. ISBN 978-0684855301 . [ page needed ]

- ^ Russell, Due north. (2012). Social Zooarchaeology: Humans and Animals in Prehistory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14311-0 .

- ^ Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Ryan, Hannah; Jamieson, Alexandra; Dimopoulos, Evangelos A.; Larson, Greger; Frantz, Laurent A. F. (2022). "Paleogenomics of Animal Domestication". Paleogenomics. Population Genomics. pp. 225–272. doi:10.1007/13836_2022_55. ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8 .

- ^ a b Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (2015). "Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside Eastward Asia: Prove from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9849P. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504236112 . PMC 4538678 . PMID26195775.

- ^ Sykes, Naomi (2012). "A social perspective on the introduction of exotic animals: The case of the chicken". World Archeology. 44: 158–169. doi:10.1080/00438243.2012.646104. S2CID162265583.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (2016). "How an aboriginal pope helped make chickens fat". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aah7308.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2002). "Evolution, consequences and time to come of plant and beast domestication" (PDF). Nature . 418 (6898): 700–707. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..700D. doi:10.1038/nature01019. PMID12167878. S2CID205209520.

- ^ Kimura, Birgitta; Marshall, Fiona; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Mulligan, Connie (2013-03-01). "Donkey Domestication". African Archaeological Review. 30 (ane): 83–95. doi:10.1007/s10437-012-9126-eight. ISSN1572-9842. S2CID189903961.

- ^ Currat, Grand.; et al. (2008). "The hidden side of invasions: Massive introgression past local genes". Development . 62 (viii): 1908–1920. doi:ten.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00413.ten. PMID18452573. S2CID20999005.

- ^ Eriksson, Jonas (2008). "Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken". PLOS Genetics. four (2): e1000010. doi:10.1371/periodical.pgen.1000010. PMC 2265484 . PMID18454198.

- ^ Hanotte, O.; Bradley, D. G.; Ochieng, J. W.; Verjee, Y.; Loma, E. W.; Rege, J. E. O. (2002). "African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations". Scientific discipline. 296 (5566): 336–39. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..336H. doi:10.1126/science.1069878. PMID11951043. S2CID30291909.

- ^ Verkaar, Eastward. L. C.; Nijman, I. J.; Beeke, Yard.; Hanekamp, E.; Lenstra, J. A. (2004). "Maternal and paternal lineages in crossbreeding bovine species. HasWisent a hybrid origin?". Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 (7): 1165–70. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh064 . PMID14739241.

- ^ Pierpaoli, M.; Biro, Z. S.; Herrmann, Thou.; Hupe, K.; Fernandes, Thou.; et al. (2003). "Genetic distinction of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Europe, and hybridization with domestic cats in Hungary". Molecular Ecology. 12 (10): 2585–98. doi:x.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01939.x. PMID12969463. S2CID25491695.

- ^ Jordana, J.; Pares, P. M.; Sanchez, A. (1995). "Assay of genetic-relationships in horse breeds". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 15 (7): 320–328. doi:10.1016/s0737-0806(06)81738-7.

- ^ Harpur, B. A.; Minaei, Due south.; Kent, C. F.; Zayed, A. (2012). "Direction increases genetic diversity of dearest bees via admixture". Molecular Ecology. 21 (18): 4414–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2012.05614.x. PMID22564213.

- ^ Barbato, Mario; Hailer, Frank; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo; Kijas, James; Mereu, Paolo; Cabras, Pierangela; Mazza, Raffaele; Pirastru, Monica; Bruford, Michael West. (2017). "Genomic signatures of adaptive introgression from European mouflon into domestic sheep". Scientific Reports. 7 (one): 7623. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.7623B. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07382-7 . PMC 5548776 . PMID28790322.

- ^ Freedman, A. (2014). "Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs". PLOS Genetics. 10 (1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170 . PMID24453982.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (2005). "Neumuhle-Riswicker Hirsche: Erste planma¨ßige Zucht einer neuen Nutztierform". Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau. 58: 255–261.

- ^ Malmkvist, Jen S.; Hansen, Steffen W. (2002). "Generalization of fear in farm mink, Mustela vison, genetically selected for behaviour towards humans" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 64 (3): 487–501. doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3058. S2CID491466. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26 .

- ^ Jones, R. Bryan; Satterlee, Daniel G.; Marks, Henry L. (1997). "Fearfulness-related behaviour in Japanese quail divergently selected for body weight". Applied Creature Behaviour Science. 52 (1–2): 87–98. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(96)01146-X.

- ^ Cieslak, One thousand.; et al. (2011). "Colours of domestication". Biol. Rev. 86 (4): 885–899. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.2011.00177.x. PMID21443614. S2CID24056549.

- ^ Ludwig, A.; et al. (2009). "Coat color variation at the start of horse domestication". Scientific discipline . 324 (5926): 485. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..485L. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1172750. PMC 5102060 . PMID19390039.

- ^ Fang, 1000.; et al. (2009). "Contrasting mode of evolution at a coat colour locus in wild and domestic pigs". PLOS Genet. 5 (1): e1000341. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000341. PMC 2613536 . PMID19148282.

- ^ Almada RC, Coimbra NC. Recruitment of striatonigral disinhibitory and nigrotectal inhibitory GABAergic pathways during the system of defensive behavior past mice in a dangerous environment with the venomous serpent Bothrops alternatus [ Reptilia, Viperidae ] Synapse 2015:n/a–n/a

- ^ Coppinger, R.; Schneider, R. (1995). "Development of working dogs". The Domestic dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425377 .

What Did Animals Look Like Before Domestication

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domestication_of_animals

Comments

Post a Comment